Crying in the Dark over The Last Showgirl

Good art about aging, show business, and beauty from Gia Coppola.

I turned 40 this month, something I’m very excited about because it feels as though I’ve finally aged into the roles I most enjoy playing: blousy aunts, head bitches in charge, ladies who lunch, etc. For the next decade of my life, I have adopted three guiding principles: good art, good money, good hangs. Much of my work on this newsletter is dedicated to helping other people up their marketing game (“good money”), but I’d like to also expand some of the work I do here to explore the work we do as artists (“good art”). As artists, I believe our work is enriched by engaging with the work of other artists. We should make it a priority not just to create ourselves, but also to consume art -- and preferably not just art in our own medium. To that end, I want to bring a bit of “good art” into this blog from time to time. So I’m starting this year with an essay on Gia Coppola’s The Last Showgirl. Enjoy.

Showbiz demands our time. When we are actively working on a show, it is difficult to do anything outside of rehearsals and performances. A night off from either is often an opportunity to prioritize self care. But I didn’t do that with my one night off from rehearsals this month. Instead, I gave my time back to showbiz and sat in a darkened theater watching Gia Coppola’s sad and beautiful The Last Showgirl.

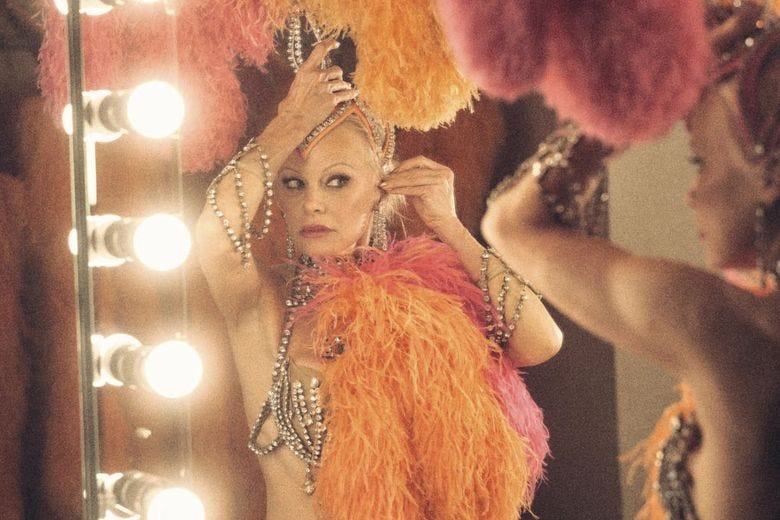

Pamela Anderson plays the titular showgirl, Shelly, who has worked in the same Las Vegas revue for 30 years. She is the last of her kind in a cast of increasingly younger dancers, and the show is the last of its kind on the strip. She is a rarity in many ways, singular even though she is no longer a feature dancer but merely another face in a chorus of 85 topless women. When the show receives its closing notice, Shelly faces a crisis point, as her sense of self, security, and value are all tied to being a Le Razzle Dazzle showgirl.

Shelly is perhaps a bit naive to think that she could remain on the show forever, or that the show would run forever. But Shelly is also a person who has fully bought into the dream of Le Razzle Dazzle. She fiercely defends the show to the younger girls in the cast who see it as just a gig. She sees it as art, which is why she is disgusted by the Magic Mike-esque chair choreography Jodie (Kiernan Shipka) demonstrates from the most popular nudie show on the strip. When Mary-Anne (Brenda Song) asserts that there is no difference between Le Razzle Dazzle and the more modern show, Shelly declares that there indeed is. She explains Le Razzle Dazzle as a descendent of the French Lido tradition and that it’s artistic, not raunchy. “It’s breasts, and sparkles, and joy!” she exclaims.

In Shelly’s differentiation between the show that has been her life for the past 30 years and the new nudie shows of a post-millennium Las Vegas, I heard echoes of burlesque legends who quit the business when burlesque theatres of the golden era dried up. Burlesque became absorbed into the strip clubs, and some dancers didn’t want to perform burlesque for strip club audiences or in the style favored by clubs. In the little time I have spent with these women, some (but not all) sound exactly like Shelly: burlesque as they knew it was different than what it was becoming.

It’s easy to say that Shelly is stuck in the past. Le Razzle Dazzle is frequently referred to as “the last show of its kind.” And even when Shelly joined the show in the 80s, Le Razzle Dazzle reflected the past by harkening back to Le Lido, the French cabaret that opened on the Champs Elysees in 1946, and whose style was emulated in Vegas revues of the city’s Rat Pack era in the 1950s and 1960s. Beyond the show itself, Shelly’s life seems to be out of date, too. She bemoans that lemons are 89 cents, when they used to cost a quarter each. Her living room pairs the paneled walls of the 1970s with couches from the 1980s and lamps from the 1960s. On her off days, she dresses in the same acid wash denim jacket and mini skirt she presumably wore when she first joined Le Razzle Dazzle. And when she goes home after the show, she sits in her living room watching archival videos of the Ziegfeld Follies or Powell & Pressberger’s The Red Shoes, taking notes on how the dancers move and dancing along with them.

But I don’t think Shelly is stuck in the past. I think she reveres it. Her intense study of the Follies, of classic ballet, and of the Lido tradition shows me that she loves the world of showgirls and glamour and that she believes it is a tradition worth keeping. While others around her -- from her estranged daughter to her coworkers on Le Razzle Dazzle -- tell her that her work is tacky or old fashioned or “just a nudie show,” Shelly believes that this is her art. She is delighted when her daughter Hannah tells her she’s majoring in photography because it means that Hannah has also chosen the life of an artist. And when Hannah says that her adoptive parents would rather she have a different job, Shelly assures her that while the life of an artist isn’t easy, it is worth it.

Shelly’s respect for her artform and her belief in its necessity, in the necessity of breasts and sparkles and joy, made the loss of Le Razzle Dazzle all the more heartbreaking for me. I openly sobbed through entire sequences of this film. I see fewer and fewer opportunities in my city for me to make the kind of art I want to make as a soloist: fewer big stages that are appropriate for acts with highly involved costumes, fewer shows that suit my style as a performer, and fewer shows in general. I find myself missing the days when my city could sustain a venerated weekly burlesque show, along with multiple shows each week from independent producers. I love burlesque and its rich history. I love teaching that history. And I love to see its influence seep into popular culture beyond the burlesque stage. I believe, as Shelly does, that there is great power in an artform that allows you to be visible and feel beautiful. And it is painful to live through a moment in which your artform seems less vital than it once was.

Shelly’s feelings of loss are reinforced by Gia Coppola’s well-composed exterior shots of the film’s characters juxtaposed against various construction and demolition sites in Las Vegas or the gleaming towers of the city’s modern casinos. The Last Showgirl is not only a portrait of an artist coming to terms with her own age and her changing industry, but a portrait of a city that’s changing and rapidly erasing its past. I thought often of a line from Wayne Kramer’s 2003 indie film The Cooler, in which Alec Baldwin’s brusque casino owner bemoans the changing city and derisively calls it an “amusement park.” Shelly tells the younger dancers that Le Razzle Dazzle’s showgirls once were flown all over the world as Ambassadors for the city of Las Vegas, literally and metaphorically linking the image of the showgirl and the city itself. This is doubly true for Shelly, who was the poster girl for Le Razzle Dazzle in the 1990s. She is the showgirl, the last ambassador to the Las Vegas of yesteryear.

If you find yourself in Vegas somewhat regularly, you know that the Las Vegas of yesteryear is by no means all gone. There are little pockets of the past all over the city, from the Fremont Street experience to the famous neon graveyard, where marquees from old casinos go to die. As much as Vegas has modernized itself, it is a city that always knows where it came from. And so it is fitting, of course, that once a year, burlesque performers from across the world commune in Las Vegas for the Burlesque Hall of Fame Weekender, which is not only the biggest competition stage in the industry, but also “the world’s sexiest fundraiser” for the Burlesque Hall of Fame Museum -- a small storefront museum that holds the distinction of being the only museum in America dedicated to preserving the history of the artform.

Going to BHOF (as we call the weekender) is a pilgrimage for burlesque artists. It is a chance to convene with artists from other cities you don’t often see, to watch some of the finest performances in our industry, and, most importantly, to connect to the women we call legends. BHOF is an opportunity to sit by the pool with a woman who worked the burlesque circuit in the 1960s or was a feature dancer in strip clubs in 1970s and learn about her life. It is an opportunity to help a retired showgirl earn a little bit of cash by purchasing a signed photo from her or one of the crafts she now sells. It is an opportunity to learn about the history of this artform directly from our legends by taking classes, attending panels, and listening to their stories. (It’s also an opportunity to see just how hilarious and vital and downright dirty many of these women are when you catch them dancing at the afterparties.)

But most importantly, BHOF gives us a chance to see our legends perform. And to watch a woman in her 70s or older perform a striptease with raw sexuality or coy dexterity is a truly life affirming experience. As the similarly-themed (but not at all similarly executed) The Substance from French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat makes abundantly clear: women are held to impossible beauty standards and all but discarded when newer, younger women come along to take our place. Watching older burlesque performers in action defies this patriarchal notion that a woman’s value decreases with age, or that we are any less sexy or less beautiful in the latter parts of our lives than we were in our earlier years.

I thought of this, too, watching Pamela Anderson in The Last Showgirl. Like her character, she is 57 years old. And she is beautiful, made up or not. Because The Last Showgirl is shot on film (16mm!), the camera is very clear about her age. Surrounding her with poreless young actresses like Brenda Song and Kiernan Shipka reinforces this perception. But I was also immediately endeared to this story because of the juxtaposition between the veteran showgirl and her younger colleagues. I thought about working with legends, about the times I’ve been backstage with them, the times when I have been the Jodie to their Shelly, helping them clasp a necklace or zip up a dress or buckle their shoes. The film’s displays of camaraderie and intergenerational friendship between dancers young and old warmed my heart, and later broke it when the loss of Le Razzle Dazzle tarnished those bonds.

To work on a show is to find yourself in a kind of ersatz family unit. Whether it’s theater, circus, dance, burlesque, music, or some other performing art, the amount of time one must spend with one’s colleagues to create the final product necessarily creates a community dynamic. We find ourselves missing our “show families” after closing. Le Razzle Dazzle’s closing notice is not only about the loss of a job (which did not come with health insurance or a pension, something the show’s union stage manager receives “just for pushing a button,” Shelly declares), but also about the loss of the family Shelly chose over her own daughter for the last 30 years of her life.

When Shelly’s daughter Hannah attends one of the closing performances of Le Razzle Dazzle, she tells her mother that she didn’t think the show was very good. And that she couldn’t believe her mother made the choice to keep working rather than getting a different job so she could raise her daughter. The film is sympathetic to Shelly and the choices she’s made. She views herself as an artist so completely that it would have been unfathomable for her to follow her friend Annette’s footsteps and retire to cocktail waitressing. And she believes so much in Le Razzle Dazzle (and is so integral to the show’s history) that she wouldn’t have moved on to any other revue. I think most viewers would agree that choosing her career over her child is not the best choice. But in the world of the film, and the realistic world in which it is set, no choice that Shelly has made in her life is a good one. But it is hard to make good choices from a menu of limited options. And so showgirls like Shelly make 89 cent lemons into lemonade and do everything in their power to keep dancing in their late 50s and beyond.

The film begins with Shelly at an audition for another show. She wears an oversized leather motorcycle cap in an attempt to both look cool and to hide her age. Later, we see this audition in full. Her routine is pedestrian compared to what we see from literal child ballroom stars auditioning for the same show. The casting director (played by Gia’s second cousin, Jason Schwartzman) cuts her off early. But Shelly isn’t keen to cede her time. She goads him into giving her feedback, and he feeds her a harsh truth as politely as one can: the skills she possesses as a dancer aren’t on par with what other auditioners are bringing to the table. There is no place for her onstage beyond Le Razzle Dazzle.

So it is to Le Razzle Dazzle that the film returns at the end, dropping Shelly into a fantasy where she is still a star, where her daughter and her daughter’s father are in the audience to cheer for her as she beams out at them bedecked in feathers and rhinestones. Even when there appears to be no hope and no future for Shelly, the film’s choice to dip from realism to fantasy in this final moment restores our hope in the power of art, and Shelly’s art in particular. Here, in this final moment, as Miley Cyrus croons “Beautiful That Way,” Shelly is beautiful and she is visible to all of us out there in the dark.

If you enjoyed this essay and want to know more about what I’m reading, watching, and seeing live, become a paid subscriber. Paid subscribers will now receive a monthly dispatch with short endorsements on books, movies, television shows, and live theatre I’ve recently enjoyed. The rest of my newsletter content remains forever free, so you won’t miss longreads like this one.